In recent months and years, there have been increasing calls to address challenges of satellite network scalability and resilience against threats, both natural and manmade. To better understand potential impact to satellite system and network architectures, we must first examine implications of the unique conditions and common use case requirements. While similarities exist with terrestrial communication network and data center evolution, the need for fluidity in how data is managed is uniquely heightened.

In this series of micro blogs on the “The Fluidity of Data in Space”, we will talk about a sequence of events that led to a revolution in how space systems are being architected for “New Space” applications, resulting in the need for onboard data storage, and why data fluidity is critical to achieve responsive, autonomous, mission-adaptive functionality for long term satellite network survivability.

- Chapter 1: Is This “Star Trek” or the Envisioned Genesis of New Space?

- Chapter 2: Data Storage Needs Grow Astronomically in Orbit. Now what? Are you going to use the power of the sun to store the data?

- Chapter 3: Data Buffers in Space or Data Centers in Space, What is the difference?

- Chapter 4: What is the ideal Memory for data storage in space?

- Chapter 5: The Fluidity of Data in Space – How Does it Enhance Satellite Survivability?

As we discussed in the first blog in this series, that fateful speech from General Shelton added fuel to the fire, further driving the evolution of the satellite network, resulting in astronomical growth in the number of microsatellites. While one could argue the concurrent progression of advanced, high-resolution sensors has increased the volume of data acquired, each microsatellite resembles its mega satellite predecessors in its ability to acquire information. What has changed is what each one does with the acquired data.

For illustration purposes, let’s examine a single satellite with a SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar) radar mapping earth, supporting our insatiable need for detailed navigation everywhere. On each orbital pass of the satellite, it will gather just over 1GB of data, which can be stored in a temporary data buffer. In the case of a mega satellite, this data would be sent back to Earth via RF link(s) for post processing. Each RF link has a capacity of ~60Mb/sec, which when compared to terrestrial communication standards, falls around a quite paltry 4G cellular link. Lasers are not a viable option for this satellite to terrestrial base station link due to atmospheric anomalies and line of sight requirements limiting viable up/down links to short sessions per day. However, lasers work quite well in outer space for satellite-to-satellite communication, raising the link layer data rate to a more useful 1.5Gb/sec rate we can move the data from one satellite and clear its temporary buffer. This combination of communication schemes works for a small mega satellite constellation as the data is never kept in space long term, which would push the boundaries of the temporary data buffer. However, it also does not allow for real time responsiveness to threats given latency-riddled topologies.

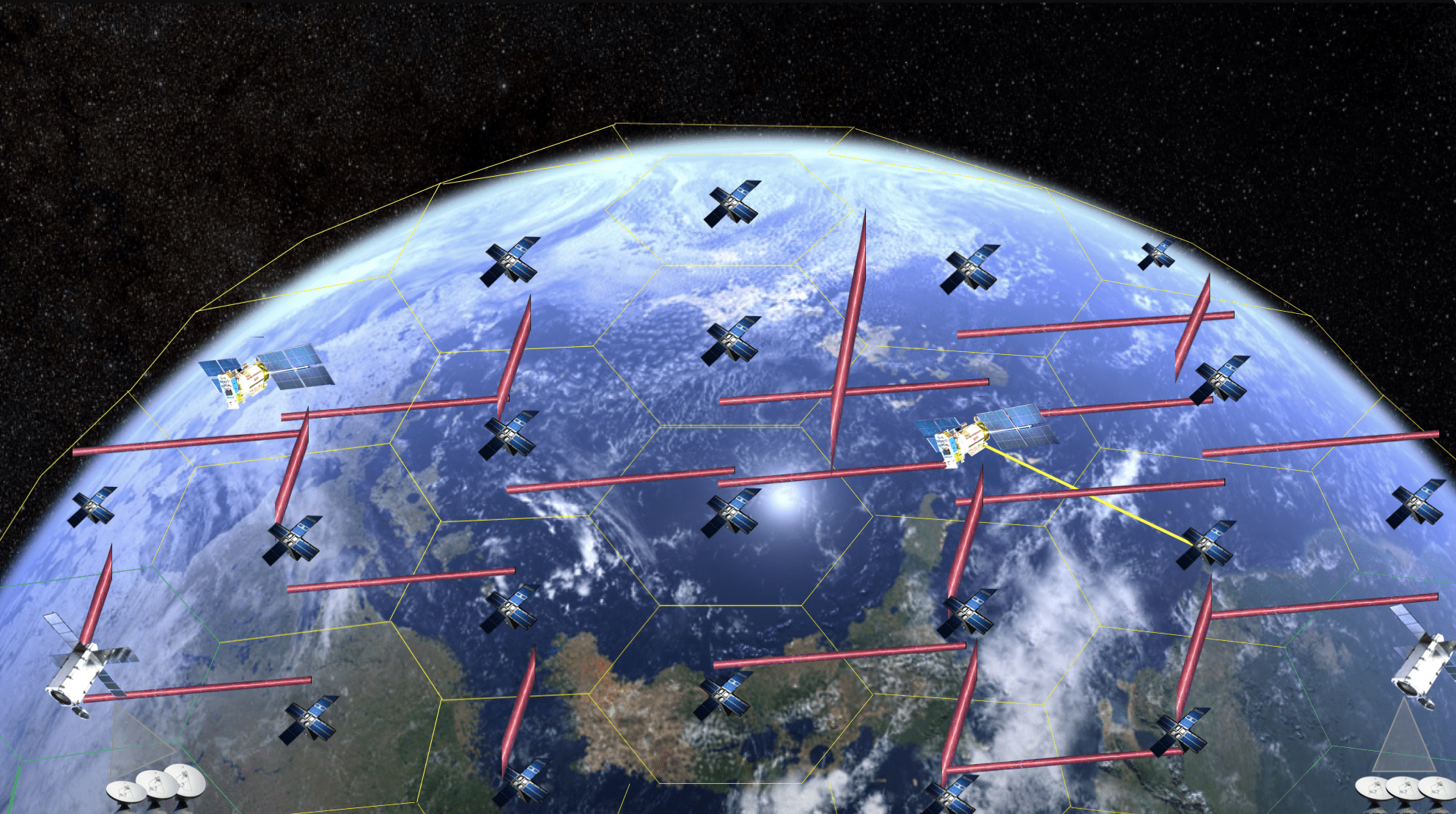

When we apply the same SAR radar mapping scenario to a “New Space” constellation with 100s or 1000s of microsatellites collecting data, scalability equations start to break down. Not only are these satellites rarely over a ground station, but they have also collected 1000 times the data (proportional to the size of the constellation), severely challenging the slow RF downlinks to Earth and the laser-linked satellite network. The result is that the data buffer becomes a permanent feature of each satellite. An example of this New Space architecture is the expansive constellation of micro satellites being deployed by SpaceX, which can communicate with one another using RF or lasers and the link to ground still limited to RF. With a whopping 100 terrestrial base stations in the SpaceX network, the communication and related data offload situation is improved, but the bottleneck largely remains, requiring the data to remain in orbit. Given this, the data in orbit now needs to be fused, processed, and acted upon in situ and then can be discarded, allowing it to avoid the communication bottleneck.

The challenge then becomes satellite-based local resourcing to support the levels of processing and data storage needed for increasingly common applications. For example, if you had 1000 imaging satellites and stored the resulting imaging data to a buffer, within one year, you would reach a staggering 5000TB. There are two common scenario sets that come to mind when looking at how this evolved satellite network architecture based upon distributed intelligence may unfold, both in terms of problems that can be solved, along with the resulting system-level architectural needs:

- For support of applications requiring analysis of patterns, such as weather, geological mapping, etc., we need to keep the data long-term for local analysis, providing an excellent case for a Datacenter in Space. This would then lead us to another discussion topic: a need for High Performance Computing and generation of AI training models in space, which will be examined in a follow up blog series.

- For situations of increasing concern due to terrestrial geopolitical challenges now spilling into the Final Frontier of space, we need to be thinking about real time responsiveness of satellites to threats, both natural and manmade. For this scenario, where we only need to look at the data for shorter periods of time a temporary data buffer will suffice. When combined with the use of AI in concert with other adjacent microsatellites, we now can dynamically respond to threats in a way that if one satellite goes down, the rest of the network can remap communication, responsibility, intelligence, etc.

In both scenario sets, the collected data is eventually discarded, so we keep the data in space, but not forever. And in the process, we dramatically improve levels of capability, autonomy, and resilience of the satellite network, while also untethering them from proximity to Earth.